THE BOOK

Introduction and Chapter 1

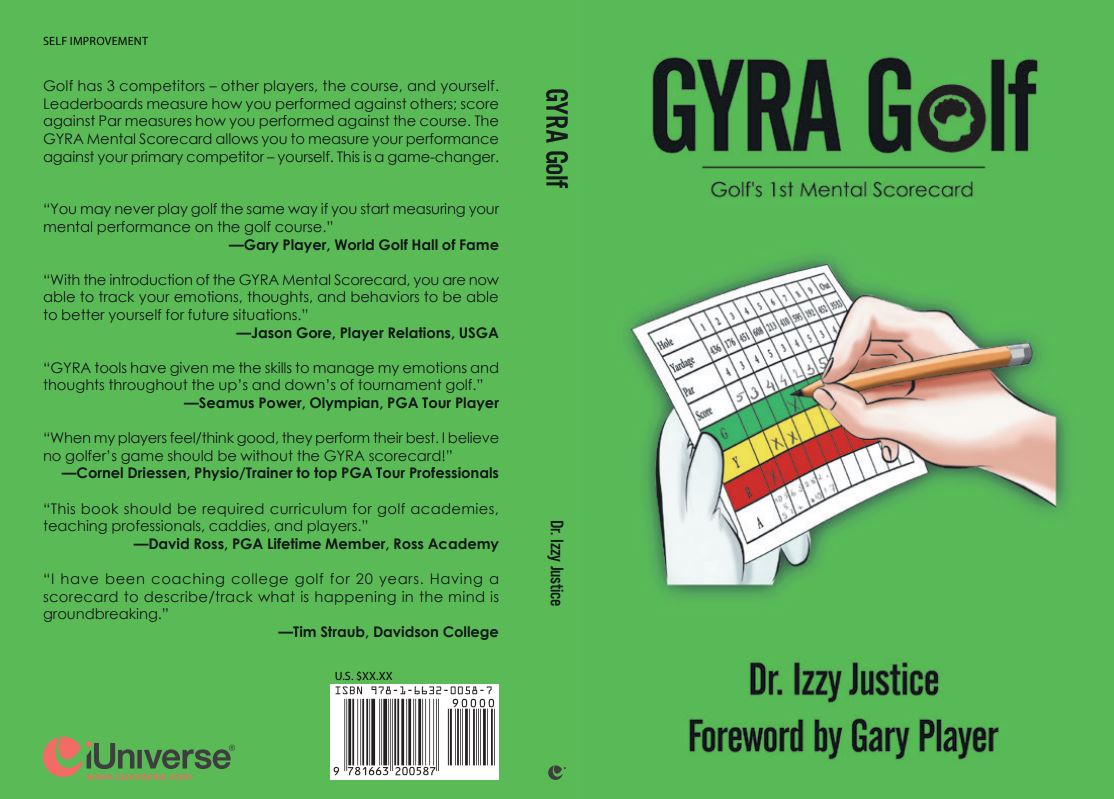

I am proud to share the first golf mental scorecard that is based on the results of a 12-month longitudinal, neuroscience-based research study on the correlation of emotional state, brain activity, and quality of golf shots. Golfers from all levels were taught an easy-to-understand model, GYRA, and asked to keep their emotional and mental score per shot and per hole on the same traditional golf scorecard. The randomized data from 500 of these scorecards was entered into a database that allowed us to draw conclusions on the impact of poor shots on subsequent shots. Certain shots correlated to half-stroke cost while others were a full-stroke cost to the overall score. I will lay out the neuroscience used, explain the GYRA model, share how costs are calculated, describe tools to use to adjust for these costs, and end with a first-hand account from a professional on how to use this model to essentially make you your own sports psychologist when you are playing so you can make better decisions and perform to your potential. To learn more, go to www.gyragolf.com.

As a sports neuropsychologist, I have worked with professional athletes, coaches, and teams in many sports, as well as with business professionals for three decades specializing in Emotional Intelligence (EQ). When working with golfers and golf instructors, I always start by asking them to describe their driver to me. Invariably, it is usually quite detailed. Most can tell me their brand, length of shaft, stiffness, flex points, club head size, loft, grip type and size, and so on. I then ask them to describe their brain. You can visualize the blank stare response. Golfers use a driver about 14 times a round. They use their brain on every shot, between shots, before a round, and after a round. It is the brain that creates the running commentary, where decisions are made on club/shot selection and course management, and where the signal is created and transported to the muscles to execute those decisions. I have found a profound deficiency in golfers in their understanding of the brain. Equally deficient is emotional literacy to label and adjust the spectrum of emotions felt through the course of a round. This book will provide that brain understanding and emotional literacy so that as a golfer, the ‘club’ you use on every shot, your brain, is as familiar to you as your driver.

It should be noted that this book is not a golf instruction book. I do not teach you how to swing any club. There is no substitute for being taught how to swing any golf club, or for a player understanding the mechanics behind a poor shot; and for that, I wish to acknowledge the invaluable role of golf teaching professionals. However, if you know how to hit a particular shot — and you have done it many times before successfully at your command — but that skill is not showing up in a critical situation, that is where this book comes in. If you find yourself saying, “I am underperforming!” or, “Where did that come from?” or, “I can’t believe I just did that!” or, “I don’t know why I did that,” then this book will answer those questions. When my phone rings, it is not because of any score that a player has just shot, it is because the player does not understand why they underperformed.

Golf Background

Golf is played in more than 200 countries. There are over 34,000 golf courses in the world. The U.S. has the most, with over 15,000. In 2005, player participation in the U.S. was at its peak, with roughly 30 million players. Shortly after that, numbers dropped steeply to around 24 million. In the last four years, the numbers have increased and are holding steady at around 25 million players.

There are 1,289 men’s college golf programs and 939 women’s programs. Division One programs have the highest number of teams from both sexes, with 299 men’s and 262 women’s programs. For these Division One programs, over $9 million are given out in scholarships combined.

The top five world golf markets are: (i) U.S., (ii) Japan, (iii) South Korea, (iv) U.K., and (v) Canada. These five markets represent 80% of total equipment sales. The U.S. and Japan control over 65% of the world market. In 2015, golf generated $8.7 billion globally.

The two governing bodies are the United States Golf Association (USGA) and the R&A. The USGA was founded in 1894 and is the governing body in the U.S. and Mexico only. The R&A was originally founded in 1754 as the Society of St. Andrews Golfers (in Scotland), and it governs the rest of the world.

One can discern from all these hard statistics that golf is a lucrative and global sport, and growing at the junior levels at an unprecedented rate. What these facts do not show is the spirit and soul of golf.

Golf is as much a sport as it is a social and business enterprise. There are vast housing developments built around golf courses so that homes can have views of fairways, greens, flowers and ponds. There are social events, such as Member-Guest tournaments, that usually are the annual highlight for most clubs. Golfers take golf trips around the country and world to build friendships and take a break from the hustle and bustle of work and family life. Vacations are planned around golf destinations that also cater to non-golfers with amenities like spas.

A ton of business is also conducted on the golf course. Corporate outings and business dealings are a norm as the change in scenery from office space is often welcome, not to mention an emotionally-disarming environment.

There is also the relaxation and physical health component that most retirees cherish. It feels great to get out of the house, and go out with little physical stress and walk on fairways. Many find it therapeutic as the social interaction with friends in an outdoor setting just feels good.

Golf as an Endurance Sport

It can be easy to forget, given all these benefits of the game of golf, that it is a sport requiring skills that has measurable outcomes. Golf, for all practical purposes, is an endurance sport. An average round of golf for 18 holes lasts about 4.5 hours. That is about the same time it takes on average to complete a full marathon of 26.2 miles, or just an hour less than a half Ironman event of 1.2 miles of swimming, 56 miles of riding a bike, and 13.1 miles of running.

What makes golf the ultimate endurance test is that it is quite literally 93% mental and 7% physical. How so? It takes anywhere between 5 and 15 seconds to actually hit a golf shot; that is, to draw a club back and strike the ball physically. With an average score of 85 shots for 18 holes, that is less than 20 minutes of physical activity. This means that for a 4.5-hour round, 4.1 hours are spent on non-physical activity that very few golfers have any plan for. It begs the question of why almost 100% of time training for golf is spent on the physical activity, yet almost no time is spent on effectively managing the large amount of time between shots?

I speak at events about 20-30 times a year and often ask golfers: What percentage of golf is mental versus physical? The lowest mental number I have heard is 60% and the highest is 95%. I have found that the better the golfer, the higher the percentage of the mental side is acknowledged. It begs another question of why, if both the quantitative time and the actual percentage of skill (60-95%) required is mental, there is almost no time spent training for this?

This book is largely about managing that 93% of time so that when you are ready to hit a shot, your emotions and thoughts are in the best place possible for the shot to come out as you want. It is about recognizing that, just because you are not hitting a shot 93% of the time, the brain is still working, processing past and future shots. If the brain is left to do what it naturally does, that is a wasted opportunity. It is about having a plan to play golf to give you the best chance of being fully ready (mentally, emotionally, and physically) to hit the next shot to the best of your ability, whatever that ability is.

The central premise of this book is that golf is as much an emotional and mental endurance test as it is a golf skill test.

In trying to understand why little to no time is spent training for the emotional and mental test of golf, of the many reasons offered and researched, I have found one cause more compelling than all others. As a tour pro confessed, “I don’t even know exactly what I’m supposed to do to mentally prepare or grow.” This is because there is no measurement of the mental side of golf.

In all sports, and golf is no different in this regard, the measurements of the physical side of the sport are abundant. In basketball, stats are provided for the number of minutes played, shots taken, shots made, rebounds, assists, and 3-points made. In golf, just go to the PGA Tour website, pick any pro, and under their profile you will find more statistics than you are likely to understand. The most common ones are score, fairways hit, greens hit, and putts made. For tour players, there are about 20 other measurements available. Because of these measurable results, it is easy to identify areas of improvement. If you only hit 2 fairways in your round, then you likely need to work on your driver. If you took 54 putts, 3 per hole, then you likely need to work on your putting. Measurements allow us to identify areas of strength and weakness, thus making it logical to know what to work on to improve.

However, as noted in the earlier paragraphs, the consensus is largely that golf is driven not by these measurable physical skills, but actually by the mental ones. In Chapter 2, I will show neurologically that, in fact, the physical golf skill rests on first the emotional and mental state of the brain. In other words, those golf statistics we measure are more dependent on other variables (emotional and mental) than on the proficiency of golf skills themselves.

What if there was a mental scorecard that allowed you to do the same things as the other golf metrics? What if the mental score per hole, and even per shot, allowed you to know exactly where you are emotionally and mentally? Could the metrics help you make adjustments while you are playing? Once the round is complete, could the mental scorecard be used to identify what to work on, to improve? Could a mental scorecard provide an answer to the tour pro’s question of knowing what to actually do to build mental strength? The answer is YES!

The emotional and mental endurance test that is golf requires a scorecard that can identify the true root cause of poor shots.

It is worth repeating the question many good golfers ask me: “I don’t even know what to work on so I can be mentally stronger when I’m playing?” If your putting is off, you have dozens of drills and training aids to help. If your bunker play is off, and the statistics show your bunker save-percentage is low, then you know to get a lesson on bunker play and work on it. If your swing is off, you may have an instructor who knows your swing and knows what is off. But in the hours of practice time you have, what exactly are you supposed to be doing to grow mentally?

This book presents what I believe to be the first Golf Mental Scorecard, called the GYRA Scorecard. I will share how to train your brain off the golf course to become mentally stronger during practice time; and how to use the score card when playing to properly identify the root cause of a bad shot (or hole or sequence of shots/holes) so that the adjustments can be made and rounds/scores can be saved.

“Crises are part of life. Everybody has to face them, and it doesn’t make any difference what the crisis is.” -Jack Nicklaus

I will also introduce you to a sequence of emotional and mental preparation, before, during, and after a round, as well as for practice. You will be introduced to a new emotional and mental language similar to the physical language of golf. In the latter, golfers know what a bunker is, what fairways, greens or rough are, and what a putter is versus an iron or a driver or wedge. We know what a fade, draw, hook, and slice are. These are all words that form a language that allow you to understand the physical game of golf. Yet, we do not even have a language to understand our own brain or emotions; words that we can use in the same way to properly label and adjust what is going on during the round.

In addition to a new language, you will build your own personal game plan. No two human beings are the same emotionally and mentally, so the plan for each person will be different and has to accommodate the emotional fluctuations of both life and golf, where highs and lows can impact so much of decision-making. I call this the “software” of each person, as opposed to the hardware, which is our physical and biological bodies, which are virtually identical in function. Your software is different from another other human in the world, even though you have the same organs and body parts as everyone in the world.

During a round of golf, the sheer volume of monologues (software) that occur is quite unprecedented. Each monologue, that self-talk and commentary, after almost every shot, is a natural human response to the stimuli of the ever-changing environment. Whether it is the tee box, the wind, the rain, the heat, the playing partner, the lie, the pin position, the inconsistent greens, bunkers, or fairways, or whatever myriad of unique circumstances that literally each shot presents, the environment in golf is constantly changing and challenging. Compound this with the competitive environment of whoever you are playing with or against, your expectations or handicap, no teammates or coaches to help you, as well as the countless things that can go wrong, we are talking about a brain that has an enormous amount of activity to process. Your software is working non-stop and largely without any proactive conscious direction from you. It is just doing its thing. The brain activity when playing competitively is not the same brain activity when playing casually, not even close. In effect, the brain used on the driving range, practice area, practice rounds, casual rounds, is not the same brain as when you play competitively, thereby making the overwhelming majority of range and practice time quite ineffective. Would you go the first tee with a set of clubs that you have not used in a while? No. This is what you are doing by not training the brain for the actual mental conditions of competition. It is why many say the hardest shot in golf is the first one off the first tee because it feels different.

These emotions and thoughts, both good and not so good ones, will dictate the tone and content of the monologues and critical subsequent decision-making throughout the round. In Chapter 1, I will share several stories that almost all golfers will be able to relate to; where they themselves got in their own way, failed to execute their strategy for the physical game, and underperformed.

Yet, despite powerful personal stories of underperformance and many more well-documented ones from professional golfers, the average golfer still spends almost zero time training his or her emotions and thoughts. I researched dozens of golf training programs and videos and found very few that had budgeted time for this kind of training.

When asked what is the most difficult shot in golf, the most common answers I get are the first tee shot or a 40-yard bunker shot, or a few will say the next shot. It is my absolute contention that the most difficult shot in golf is the one right after a bad one. Why? As I will explain in Chapter 2, right after a bad shot, the emotional temperature is so high that cognitive decision-making is neurologically compromised, leading to a very low probability that you can either make the right next decision or physically execute that next shot to the best of your ability. What shows up as a “bad shot” was actually caused by the brain processing the previous shot, unable to focus on the shot at hand. Golfers have had no way to measure the emotional/mental cost of that previous bad shot. Not all bad shots have the same cost. Missing a two-foot putt for birdie is not the same as missing a two-foot putt for bogey. Even though both are equal in stroke count, they are not emotionally/mentally equal. Both are costly, but the latter is much more expensive. Making a double bogey feels much worse than making par in terms of cost. The GYRA Scorecard creates an Emotional and Mental Accounting System that allows you to assess the correct neurological cost, and then make the right adjustment to redirect the brain so that the cost is never high enough to impact the next shot.

“It’s easy to hit a great shot when feeling good, it’s really tough to hit a good shot when feeling bad.” -Bob Torrance

This is the reason to write this book: to allow golfers to measure each shot and each hole with a score that can best reflect the mental cost and state, so that they can go to the next shot and execute it to their best.

This book is not about swinging the golf club correctly, putting correctly, getting more distance or the short game, nor is it about any equipment. There are plenty of resources for these dimensions of the sport that are readily available. Golfers are notorious for buying anything that they believe will make them perform better, but there is no off-the-shelf equipment for rewriting your software to manage your thoughts and emotions. This is a personal endeavor.

“Every man dies. Not every man really lives.” -William Wallace

This book brings decades of experience and neuroscience working with elite athletes, coaches, golfers, and amateurs. I hope this book will be an invaluable asset to your practice and round of golf. I will start the book with real-life stories to prove that golf is indeed an emotional and mental test, more so than physical. Then, I will provide you with detailed and easily understandable neuroscience of how the human body works: what emotions and thoughts are and how they are created; and how to recognize, label, and manage them during practice, pre-tournament anxieties, and each situation in your round. The chapters will build GYRA tools, 14 of them, like a set of clubs, to use to make adjustments. Finally, a tour player will take you through a full week of how the GYRA scorecard and tools were used in a pressure environment like Q School.

You will learn not just mental tips to be a better golfer, but also understand why that tip will work for you from a neuroscience perspective. The explicit intention is that you fully understand why these tips work so you can make adjustments as warranted, instead of just doing random things and hoping they work. This combination of knowledge is guaranteed to help you with your goals, and almost surely, with your personal journey of growth as well. It will answer the question, “What can I do to grow mentally?”

The goal of this book is that you will use the GYRA Scorecard, conveniently identical to the traditional scorecard of any golf course, in all your rounds to help you win the first challenge of the test of golf – your emotional and mental state. Winning this will allow you to showcase your golf skills when it counts the most.

Essentially, two books are being provided to you – one that I wrote, and the other written by you in the spaces provided in this book because your software is unique to you and only you. Thus, if you do all of the written exercises suggested, you will have a second book written by you, and for you. Either or both of these books can be read many times over during your season. Your book will provide you the necessary emotional/mental “clubs” to use per situation that are unique to you so that you can use them while using the GYRA Scorecard.

Emotional endurance and mental strength are not just a part of golf, but also a part of life. It can be argued that life itself is an emotional endurance test. And this may be what makes golf so popular, as you can draw parallels between training for and playing a round, and your own life’s journey. It is possible to feel many highs and lows and everything in between in a round of golf – a microcosm of life. I hope that the reader-interactive format will impact both your physical and emotional endurance to help you perform to the best of your ability when it counts the most.

- The question is never, “What do I feel?” It is, “What memory of mine is being associated with this experience?”

- Neurologically speaking, life can be effectively described as a series of biased interpretations of experience. As awful as this sounds, it does suggest that if interpretation itself can be altered, and not experiences, life can be quite different.

- I often ask a trick question to athletes: What do you do if you want to get to really know someone? I always get good responses. I then ask: How many of those things do you do to get to know yourself? In the middle of competition is not the right time to learn about yourself!@izzyjustice

Why Train in EQ?

So why invest in learning about the brain and Emotional Intelligence (EQ)? I recognize that you are already spending hours on the range, on the putting green, in the short game area playing with 14 different clubs, each of which you can use to hit a variety of shots depending on grip, swing, force of strike, and so on. There is a lot to practice in the physical game of golf and shots to have. There are also all the equipment changes that come out every year from clubs to grips, balls, and so much more.

So why add yet one more dimension to your practice plan? Perhaps the best way to establish the case for this is to review several examples of what happens all the time in golf and other sports. Below are actual stories by professionals and amateurs alike. I had literally hundreds to choose from, but selected just a few that underscore the fact that mis-hits (bad shots) are virtually guaranteed to occur in golf, and it is your emotional response to them that can be the difference between underperforming and recovering to overachieve.

“I think maybe I hit only one perfect shot a round.” –Jack Nicklaus

- In the 1989 Masters, Scott Hoch had a one-shot lead with two holes to go. As he walked to the 17th tee, he said he started thinking about winning the tournament for the first time. He hit his drive into the 15th fairway, from where he said he made a mental mistake by trying to hit his second shot all the way back to the flag instead of leaving it underneath the hole like he knew he should have. He hit it over the green and missed a short putt for par.

He ended up in a playoff with Nick Faldo. On the first hole of the playoff, number 10, Hoch hit a perfect drive and second shot in the middle of the green, while Faldo hit it in a greenside bunker and made bogey. Hoch had to two-putt an uphill 20-footer for the win. He ran his first putt two and a half feet past the hole and had a downhill left-to-right breaking putt for the win. He recalled that on the 17th hole, he had backed off his short par putt, which he missed. On the playoff hole, he said that he wanted to hit the breaking putt firmly, so as to eliminate most of the break, but he was not comfortable over the ball and knew that he was aiming too far to the left for the speed he wanted to hit the putt with. He said that he did not want to back off again because of what happened on 17, so he continued on. Everything seemed to be going too fast. He ultimately hit the putt too hard for where he was aiming and missed the putt that would have won him the tournament. He then lost the playoff on the next hole.

Analysis: The emotional anxiety of potentially winning led him to hit his shot on 15 farther. The emotional memory of the putt on 17th compromised his ability to hit the putt harder on the playoff hole. High negative emotions redirected his neuropathways (thinking routes in the brain) so everything appears faster as fewer options are explored. The challenge was not physical, it was mental/emotional.

- In the 1970 British Open at St. Andrews, Doug Sanders had a two-foot putt on the 18th green to beat Jack Nicklaus by a shot. Sanders said that, over the final three holes, he was already thinking that he had won the tournament and how great it was. On his two-footer on 18, Sanders took an inordinately long amount of time over the ball. Before he took the putter back, he was distracted by what he thought was a small pebble between his ball and the hole. He bent down to pick it up, only to realize that it was just a piece of discolored grass. Instead of going through his normal routine again, he went straight back to his stance over the ball. He said he could hear people in the gallery laughing and he thought to himself, “I’ll teach them to laugh at me,” instead of thinking about his putt, which he ended up missing. He lost a playoff to Nicklaus the next day and never won a single major championship.

Analysis: Hitting a two-foot putt was not the issue. Allowing his focus to wander was. The challenge was not physical, it was mental/emotional.

- In the 1961 Masters, Arnold Palmer was leading Gary Player by one shot when he hit his drive to the middle of the fairway on 18. It was going to be his third Masters in four years. His good friend, George Low, was in the gallery at the spot of his second shot and congratulated him on his victory. Palmer proceeded to hit his shot into the greenside bunker and make a double bogey to lose to Player by a shot. In many interviews Palmer has given since regarding that loss, he regrets how his emotions got the better of him with the congratulatory comment.

Analysis: Even for the most talented and skilled golfers, vulnerability to unwelcome emotions and thoughts is high. The racing thoughts in his head over-powered the ability to hit the desired shot. The challenge was not physical, it was mental/emotional.

- In the 1999 British Open at Carnoustie, Jean Van de Velde held a three-shot lead on the 18th tee. Knowing that he only needed a double bogey to win, Van de Velde hit a driver off the tee instead of a 3-wood or even a long iron for safety. He hit it so far to the right that he luckily avoided the water hazard to the right of the fairway and ended up on the 17th hole. When the camera man zoomed in on his face after the tee shot, Van de Velde put his hand over the lens in embarrassment. After the fortunate break off the tee, he merely needed to pitch the ball back to the fairway and then play to the green from there. He later said that he did not want to win that way, by pitching back to the fairway, and instead wanted to win with a flare by hitting a 2-iron over the hazard in front of the green. His 2-iron flew into the grandstand to the right of the green, ricocheted off a metal pole, hopped off the rock wall of the hazard, and buried itself in a miserable lie in the waist high rough, still not over the water yet. Again, instead of pitching the ball sideways, he tried to go over the hazard, but did not hit it hard enough and hit it right in the middle of the water. After a drop, a pitch that found the front bunker, and a bunker shot, he ended up having to make a 7-footer for triple bogey just to get into a three-man playoff, which he eventually lost.

Analysis: Pitching the ball back in play was the right cognitive decision with the lead he had. His emotional desire to look heroic in victory trumped an otherwise simple decision. The challenge was not physical, it was mental/emotional.

- In the 2016 Masters, Ernie Els was playing his first hole of the first round. After missing the green and chipping up to three feet, Els experienced one of the worst cases of the yips that have ever been seen. Just the previous week in Houston, he had led the field in putting from inside of 10 feet. His stroke on the first green was so shaky and violent that he never even came close to hitting the hole on his 3-footer. He did the same thing on the comeback attempt from two feet and ended up missing three more times from less than three feet. He ended up six-putting the hole for a score of nine, and ultimately missed the cut. He admitted after the round that his game coming into the week was very sharp and he put a lot of pressure on himself to win a tournament that he desperately wanted to win in the late stages of his career.

Analysis: With each miss, it was less about a two-foot putt and more about the emotion of failure which diluted his focus on a routine putt. The challenge was not physical, it was mental/emotional.

- At the second stage of the 2012 PGA Tour Qualifying Tournament, a mini-tour player had finally gotten off to a solid start at the stage that had been his stumbling block to getting back out onto a major tour. This was the last year in which a player could play their way straight onto the PGA Tour, but still with the consolation prize of assuring membership on the Web.com Tour. Through two rounds, he was nine under par and had only made a single bogey.As he sat in the hotel room that evening, his mind started thinking ahead to how great it would be to at least get back out on the Web.com Tour, where he had not played since 2007. He was well inside the cut number and playing nearly flawlessly, so he was essentially planning his schedule out for the next year.He was paired with two high profile players in the third round and felt like his brain was in a cloud all day. He was caught up in comparing his game to theirs and began hitting poor shot after poor shot. He shot 74 in the third round to put himself on the cut line. He was again paired with two notable players in the last round, and was again playing in a mental fog. He shot 75 in the final round to miss advancing.

Analysis: There are three competitors in golf in this order: (i) you, (ii) the course, and (iii) other golfers. The emotions of playing with two better-known players reversed the order of importance and focus. The challenge was not physical, it was mental/emotional.

- In the 1991 Ryder Cup at the Ocean Course at Kiawah Island, Mark Calcevecchia was playing against Colin Montgomery in the Sunday singles matches. Calcavecchia was four up with four to play and knew that even a half point either way could win or lose the Cup. Montgomery won the 15th and 16th holes, but hit his tee shot in the water on the par-three 17th. Needing only to hit the ball on dry land, Calcavecchia topped his tee shot into the water. After both dropped and played to the green, Calcavecchia needed a two-footer for a double bogey that would tie the hole and win the match. He missed the putt and lost the 18th hole as well to end up halving the match. After suffering what appeared to be a panic attack in the minutes following the match, Calcavecchia said that he had suddenly felt the entire weight of winning the Ryder Cup for his teammates when he was ‘4 up with 4 to play’ and it became too big for him.

Analysis: The “weight” he is talking about is nothing more than the extreme emotional condition of that moment. The mistake was not in feeling that, but rather in not knowing how to deal with it. The challenge was not physical, it was mental/emotional.

- A junior golfer had an AJGA tournament where several college coaches would be in attendance. She had been playing very well and had a great practice before the round. To her surprise, when she walked up to the first tee, virtually all the coaches were there even though several groups had already started before her. She had played in front of people before, but she said she had never felt so many eyes on her and became aware that every single thing she did on that tee box would be analyzed. She proceeded to block her shot out of bounds and never recovered. For the remainder of the round, she was more anxious to finish and get out than to try to recover and salvage a decent score.

Analysis: Her issue on the tee box had nothing to do with all the practice she had done on her physical game. She told me later she never practiced for a moment like that and had no idea how to process all that stimuli in her head. The challenge was not physical, it was mental/emotional.

- In the 1996 Masters, Greg Norman held a six-shot lead going into the last round. The Masters was always the tournament that he wanted to win the most, but it was also where he had suffered the most crushing defeats of his career in years past. He had played flawlessly in the first round, tying the course and major championship record of 63. His play had become more ragged over the next two rounds, but most analysts were still practically conceding him the tournament with 18 holes to go. In an interview almost 20 years later, Norman admitted that when he woke up Sunday morning, he could sense that he was “off”. He said that he was struggling with an off the course issue that was at the verge of boiling over, yet he never told anyone about it. On the range before the round, he admitted that he was panicking, despite his coach and caddie both telling him his swing looked perfect. On the course, he opened with a bogey and made mistake after mistake, eventually shooting 78 and losing by five shots to Nick Faldo.

Analysis: We are human beings with one brain. There is no way to compartmentalize personal life from golf as it is the same brain that houses all experiences and memories. Personal life has arguably the largest emotional impact on a golfer because golf is a non-reactive sport (unlike basketball or tennis) where most of the time (93%) is not on the physical game. The challenge was not physical, it was mental/emotional.

- In the 2016 Masters, Jordan Spieth was attempting to become the fourth player in history to win back to back tournaments, as well as his third major championship. During the final round, Spieth made four consecutive birdies from holes 6 to 9 to open up a five-shot lead with nine holes to play. After playing his most solid nine holes of the tournament, Spieth later said that he started the back nine just trying to make pars to protect his lead. He began to hit poor shot after poor shot and made two bogeys in a row before hitting his tee shot in the water on number 12. After taking his drop, he proceeded to chunk his third shot into the water again and made a quadruple bogey. He ultimately lost the tournament by three shots. When later asked what his thinking was during those shots in the water, he said, “I don’t know what I was thinking. It was a tough 30 minutes that I hope I never experience again.”

Analysis: “Not being able to think clearly” is the sure sign that emotions have taken over, not that you cannot think. Managing emotions well is determined by how quickly you can think clearly again after a bad shot. The challenge was not physical, it was mental/emotional.

- In 2014, a new reality show came out, called The Short Game. The show documented a group of junior golfers, ages 7 to 9, and their parents, as they prepared for and competed in tournaments around the country. In most of the cases, a parent would caddie for the child during the competition and would very often harshly criticize and yell at the child after he or she made the first mistake of the round. This more often than not would trigger a tailspin of worse shots by the child and even harsher criticism from the parent, leaving the child in tears before the round was even over. The children in those situations never showed any signs of improvement during the season and often appeared to resent the game as well.

Analysis: Experiences are stories told using words in monologues in our minds. Each carries an emotional value especially from people of importance in our lives. For kids and young adults, golf is mostly emotional as what it means to self-esteem and acceptance by others matters more. The challenge was not physical, it was mental/emotional.

Clearly, there are hundreds more of these kinds of stories that can be shared. And it is not just in golf.

Other Sports

Athletes from all sports experience similar surprises, setbacks, and losses that are not attributable to the athlete’s physical or technical skills. What must be noted in these other sports and athletes is that the common thread is how all athletes are, first, human beings built with the same physiology and neurology, and exhibiting the same emotional responses as golfers.

- A basketball player practices free throws thousands of times and makes all of them, yet something is different when the free throw has to be made with one second to go and the game is on the line. What is different? Is it the size of the basketball? The size of the rim? The distance to the basket? Did the basketball player suddenly lose weight or get shorter or lose 20 IQ points? No, of course not. What is different is the pressure of the situation – the emotions of the situation. This is not physical, it is emotional.

- At an Ironman event, a pro athlete was leading the race until about mile 16 of the run when another pro athlete passed him. He had led the entire race and was shocked to get caught. So disheartened was he by this, that he decided to try to keep up with the new leader and go faster than he knew he could. Intellectually, he knew that he could not keep up the faster pace this late in the race but chose to ignore this, and push himself even harder. By mile 22, he was spent, and instead of a certain second place finish, he ended up 12th. After the race, he was visibly upset. He just could not understand why he reacted the way he did when he got passed, why he abandoned his race strategy and how he let his emotions at the time cause him to ignore his training, and instead, adopt a totally unrealistic running pace. He clearly underperformed and it had little to do with his physical skills.

- A NASCAR driver and his crew chief tell me that the race is called and raced differently in the first 200 laps versus the last 50 laps. The difference between the winner and the next 10 drivers is literally seconds, so the last 50 laps are critical for finishing position. But the track is the same as it was in the first 200 laps. What is different is the pressure of those last laps where critical decisions are made. Those last laps are no longer about cars and all about the decisions the driver and crew chief make. It is not about the equipment, but the emotions of the situation.

- A professional tennis player tells me the difference between the first four sets and the fifth set is just one thing: mental strength. She says it almost ceases to be about tennis, and whoever can remain calm in the moment of pressure and execute the shots they know they have hit thousands of times before in the fifth set almost always wins. What is the difference between the sets? What is different is the pressure of the situation – the emotions of the situation.

- The New York Knicks had a 105-99 lead with just 18.7 seconds left before Indiana Pacers’ guard, Reggie Miller, sent them falling into one of the most stunning end-game collapses in NBA history by scoring 8 points in nine mind-blowing seconds. Miller began by hitting a 3-pointer. Then he stole the ensuing inbounds pass and dashed back out to the 3-point line, where he wheeled and drained another 3 points to tie the game at 105. “We were shell-shocked, we were numb,” Knicks forward Anthony Mason remembered years later. “We became totally disoriented.” The Knicks still had a few more chances to win, but John Starks missed two free throws, and Knicks center, Patrick Ewing, missed a 10-footer before Miller was fouled on the rebound. He made both free throws to give the Pacers a shocking 107-105 win, and then he ran off the Madison Square Garden floor yelling, “Choke artists!” The Pacers went on to win the series in seven games.

— Johnette Howard

Terms like “shell-shocked” and “disoriented,” used by the Knicks and so many other athletes in all sports to describe how they felt, are lay terms, in effect conceding that something happened to them that they cannot explain. For any athlete, golf or other sport, there should be no part of his or her performance that he or she should not be prepared for, much less not be able to explain.

It should be noted that there is a fundamental difference between these kinds of stories of underperformance and others where athletes underperform because of physical reasons. If you have a strained back, it is going to be tough to hit the shots you know you can hit no matter how much emotional strength you have. When something irreparable happens to your body, no amount of EQ can compensate for that. Similarly, if you do not have the skill to do something in practice, then no amount of mental strength can create that skill on the golf course. If you do not have a high draw in your repertoire and never hit that shot successfully on the range, you simply cannot “will” yourself to do it.

As a neuro-sports psychologist, I have found that disappointment and frustration do not come from failing to execute on something never done before. They come from underperformance, the inability to execute on the very things you have done many times before, but not when in matters most: during game time. It is the examples given above that are much harder to swallow because you feel it was something mental, and the root cause of your poor reaction is still inexplicably a mystery to you. In these underperforming situations, you feel like you lost control and let something derail you. You feel like you beat yourself. This is where neuroscience and EQ can make a tremendous difference.

“What separates great players from the good ones is not so much ability as brain power and emotional equilibrium.” -Arnold Palmer

So Why Train in EQ?

As described above, rounds of golf are littered with these stories of self-inflicted wounds where the mind inexplicably chose to make poor decisions in the heat of battle during ‘game time’, and in many cases, decisions that were contrary to what they and their coaches had already agreed on during training. Why did their minds deviate from their strategy? Why did they react in a manner where, in hindsight, and with a much clearer mind, they would have all made different and better decisions? What is it about golfers’ emotions during anxiety situations that shut down very logical decision-making, decisions that they can make on any other day without blinking an eye? What could they have done during practice to prepare them for the “heat of the battle” scenarios?

In all sports, if athletes are able to maintain composure, access their training memories, and simply perform as they have trained, then their chances of being successful go up significantly. This is obvious. How to do it is not so obvious. This is why we train in EQ. We need to understand exactly how our brain works and what our brain is doing in those situations so that we can change it. Arguably the worst feeling an athlete can have is performing poorly during game time and have no idea what is going on in his or her mind and body. We need to prepare ourselves to stay focused and positive in the midst of surprises and distractions so that we can perform our best – be it on the golf course or in everyday experiences.

The reality is that golf is a game of surprises.

Since golf is full of surprises, and surprises are processed in the brain, it is, therefore, a game of mental/emotional strength. This is a learnable skill, like any other, and is required 100% of the time you are playing golf, be it over a shot or in between shots. This fundamental shift in reframing how you view and play golf is the first step in building your Golf EQ and using the GYRA Scorecard.

I define mental/emotional strength as the ability to recognize and convert negative thoughts/emotions to positive ones.

Note that mental/emotional strength is different from being in a zone. I will discuss the latter in the next chapter. My contention is that not only can these surprises be managed differently during a round, but in fact, you can effectively train for them and increase your EQ. It is impossible to predict what is going to go wrong and when it will happen, but suffice it to say, in all likelihood something will happen that will cause anxiety just before or during your round. This we can all agree on. And if you concede this, then, in order to perform at your best on game day and hit a shot that counts, your practice must prepare you to manage your emotions and thoughts.

A plan that incorporates mental training will help you manage the unpredictable but certain to occur anxiety-inducing experiences, and your responses to them. As noted in the introduction, if you are going to spend so much time and money desperately searching for a perfect swing and shot, why not spend just a few minutes a day to grow your EQ and remain positive and focused in the throes of situations that are beyond your control? No one wishes for chaos of any kind during a round, but a positive recovery from a bad situation can actually be incredibly motivating and powerful to spur you on to an even better performance.

“Competitive golf is played mainly on a five-and-a-half-inch court, the space between your ears.” -Bobby Jones

Please take a few moments to write down in your own words an experience where you underperformed in a round, similar to the stories shared earlier in this chapter. In subsequent chapters, as tools are shared, you will be asked to come back to this story and personalize your learning. By writing down your own personal experiences, your own emotions and presence in the experience will make the learning and subsequent growth a much richer endeavor. As you write your story, try to describe yourself emotionally, mentally, and physically, as well as the situation you were in as graphically as you can.

Note that a surprise is not just a situation where something has gone terribly wrong, like the stories described earlier, but surprises can be anything where you have lost your focus and as a result, deviated from your capabilities and underperformed.

GYRA GOLF

A Neuroscience-based approach to Golf's Mental Game

“The central premise of this book is that if a golfer can measure their emotional and mental state in golf, the two most constantly-changing variables when playing, and make the right adjustments to both, then performing to the best is achieved.”